THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO BEARDED DRAGON MUTATIONS AND GENETIC TRAITS

A large number of mutations have been discovered that effect a bearded dragons appearance. In this article I will show you exactly what each of these mutations are, and how to identify them. All of the discovered mutations are covered.

I will also tell you about the terms that some breeders use that are only confusing or misleading. Some of these terms result from misunderstanding of bearded dragon genetics. Other times they are used to be intentionally misleading.

A mutation is a change that occurs within DNA that can then be passed down to future generations. The mutations discussed in this article all produce interesting visual changes to the bearded dragon’s basic appearance.

Only by learning what each mutation means and how to identify them, can you protect yourself from breeders that mislabel their animals. This knowledge is also essential to fully appreciate these reptiles.

This guide is meant to be easy to read. So you won’t find any complex genetic terminology here. What terminology we do use is defined in basic terms.

HYPOMELANISM

Hypo is short for hypomelanism, which literally means “less melanin”. Melanin is a pigment that is found all throughout the animal kingdom. Melanin can take several different chemical forms, which each have their own unique color, but it is usually brown or black (it can also be red, but don’t worry about that).

The hypo trait in bearded dragons is a recessive mutation that causes the dragon to produce less melanin. Recessive means that the dragon will only display the visual signs of the trait if it receives that trait from both of its parents. If it receives the trait from only one parent then it will only carry the trait and will not have any of the visual signs.

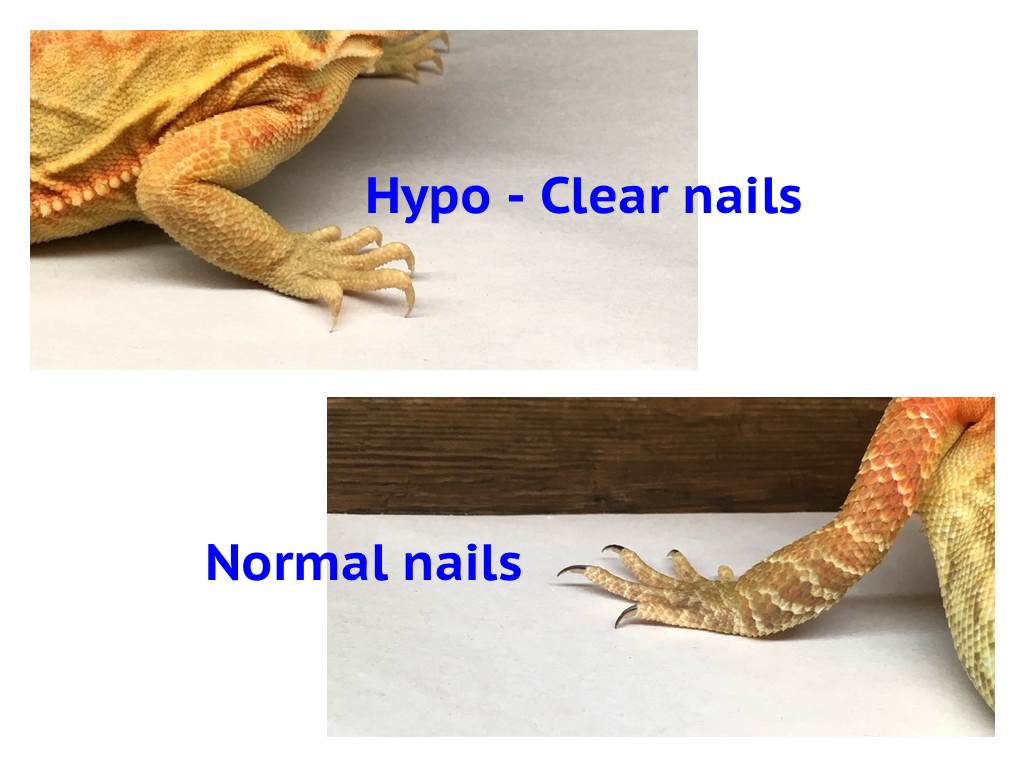

Hypo bearded dragons have clear nails without the usual brown stripe of melanin running down the top of each nail. The hypo trait also helps to reduce the amount of melanin in their scales so that other colors appear more vibrant.

TRANSLUCENT

Trans is short for translucent, which means to be transparent or see through. It is a recessive mutation that causes a partially see through skin, and solid black eyes.

Trans hatchlings have blue underbellies caused by a black lining of their internal body showing through their partially translucent skin. They can also have a blue tint in other areas, especially to the skin above their eyes. This blue color tends to disappear as they grow and their skin thickens, but some dragons retain some of this blue throughout their lives.

The trans hatchling shown above has solid black eyes and a blue belly. You can see where the black membrane lining the inside of his abdomen ends just above the legs. That black membrane makes the skin appear blue. Where it ends the skin appears white or flesh toned.

Trans dragons typically have solid black alien looking eyes, with no visible iris or yellow coloring, but this is not always the case. Trans dragons can have completely normal looking eyes, or eyes that are only partially darkened and still show some areas of gold iris. They may also have one black eye and one relatively normal looking eye.

The eyes of trans dragons can also change dramatically as they mature. Over a period of a few days their eyes can change from solid black to looking completely normal. Their eyes may then darken again, and continue to change back and forth until settling on a final appearance. The exact reason why the trans mutation causes these changes to skin and eye color are unknown.

Sometimes the term ‘partial trans’ is used to describe dragons that do not have fully black eyes. This is a misunderstanding of the genetics and only creates confusion. There is no such thing as a partially trans dragon. A dragon that is homozygous (received the trait from both of its parents) for the translucent mutation is trans regardless of the exact appearance of its eyes.

With any of the mutations discussed in this article, there are A-typical examples. An animal is A-typical if it expresses one of these mutations, but not in the perfect, standard way. The presence of other genes can effect the expression of a mutation, but there is no mutation that is ‘partial trans’.

A final word on trans dragons… don’t believe every thing you read.

Today the internet is filled with out of control myths and gossip about the trans gene. Just about every health issue imaginable has been wrongly blamed on the trans gene with zero data to backup these claims.

The often repeated myth is that if two trans dragons mate, the offspring will be weak, sickly, or have any one of a long list of health problems as juveniles, or appearing only when they become adults. None of this is true. But it has been repeated so many times that it is only natural that many people believe it is true.

There was a point many years ago when trans dragons were being overbred to produce dragons with a full body blue or purple tint. That project was eventually abandoned by breeders because those dragons did indeed have health issues.

That was a long time ago. The trans gene is now one of the oldest of the mutations, and has long since spread to every corner of the gene pool. Yet the myth continues to be repeated.

The only solution to a problem like this is to have real data to separate the facts from the myths. So we performed a study. We compared the dragons that we produced from trans pairings, to trans dragons that we produced from other pairings. And we included enough pairings in the study to provide statistically significant results.

The data confirmed what we had already seen: That our trans pairings produce strong, healthy hatchlings, that grow up into strong, healthy, fertile adults, who also go on to produce strong healthy hatchlings. We couldn’t find any data at all to justify the idea that two trans dragons produce offspring that have more health issues than other dragons at any stage of life.

In fact, some of our trans pairings produce some of our best offspring. And interestingly, plenty of breeders have told us they feel the same way. Any breeding pair has the possibility of producing genetically weak offspring of course. But is the trans gene responsible?

Of course not. Genetics is far more complex then that.

This topic and the study we performed go far beyond what we can include in this guide. If we did, then we would never get to move onto the rest of the mutations. That is why it is the subject of an up coming article we are working on. More to come soon.

PARADOX

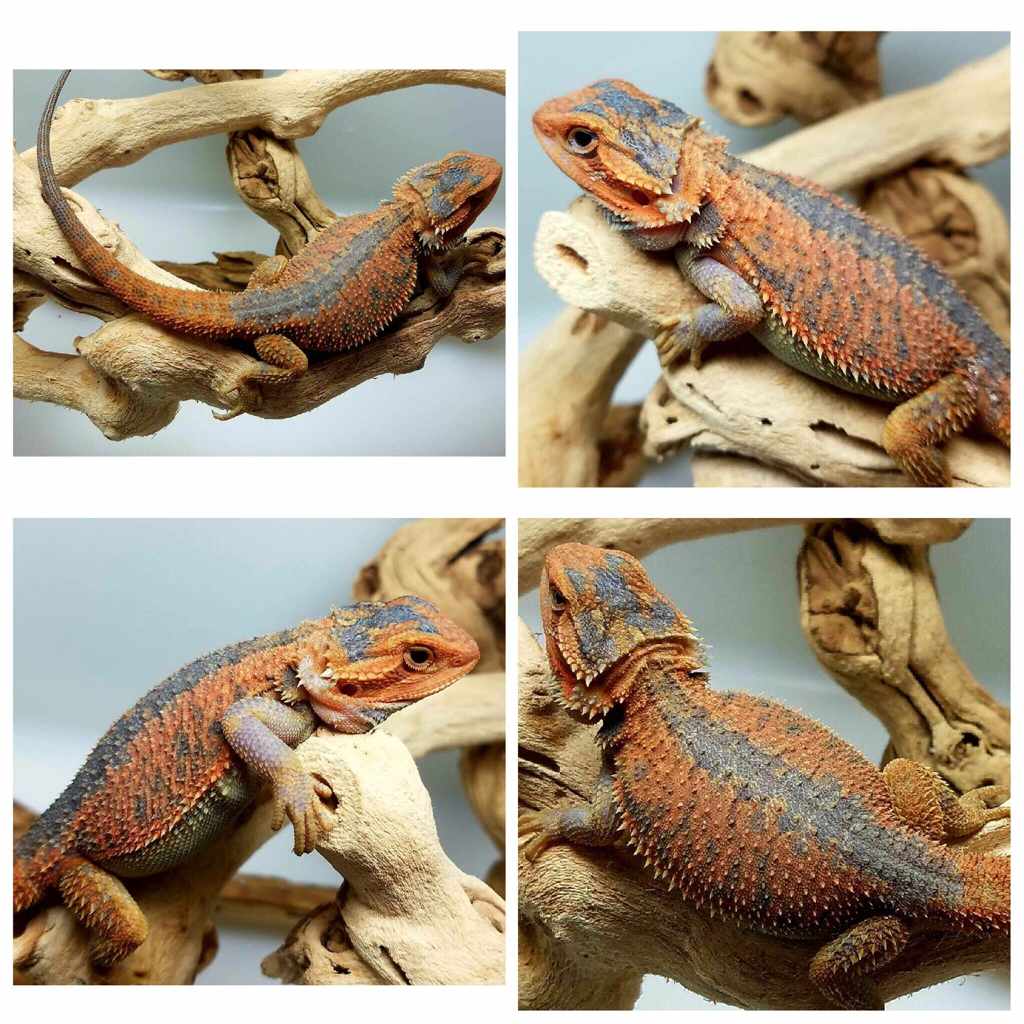

Paradox bearded dragons are some of the most beautiful, rare, and sought after dragons. Paradox bearded dragons have patches of color that appear to occur randomly anywhere on the body, with no pattern or symmetry to them. They often look as if paint splattered on them, leaving patches of color wherever the paint happened to land.

Above is Elsa, one of our breeders, when she was still a juvenile. Her front arms transition sharply from her base color of red, to yellow, and she has paradox spots of blue over most of her body, and lavender on her arms. As she matured, the blue and red seemed to compete within each scale and spike, leaving each of them with at least some blue, or looking green where the blue and yellow coexist.

Paradox dragons can be any color. Some breeders refer to them as “purple paradox”. Throwing the word purple into the name is just a trick to make them sound more interesting. Paradox dragons don’t need any tricks to make them sound more interesting because they are already to coolest dragons out there!

But if they are purple, then why is it a trick to call them purple paradox?…

Because most of them aren’t purple. The bizarre patches of color that appear on paradox dragons can be blue or purple. Blue and purple are so unique that they have become known for it. But they can have patches of any color and most of them are not purple or blue.

In fact, color wise some paradox dragons are downright drab. They are awesome anyways just by being paradox. Kismet, another of our paradox breeders is shown above. She has a brilliant red base, but her paradox spots are black and grey rather then blue.

The quality of paradoxing has two measures. The first measure is color. The second measure is how much of the dragon is covered with paradox color shifts.

The best dragons have vibrant colors and lots of distinct paradox patches. But a dragon that is low in one measure, may still be highly sought after by being high in the other.

Dragons do not hatch from their eggs looking paradox. They start out looking completely normal. The color shifts develop in the first few months of life. When the transition is finished, the dragon can look very different then the colors he started out with.

The paradox trait is not entirely well understood because it is not caused by any one single genetic mutation. The other traits discussed in this section are each caused by one specific mutation. No one yet knows how many genes go into the development of paradoxing.

The only known gene that paradoxing has been closely linked to is the trans gene. There is a whole history behind how the trans gene gave rise to the latest paradox dragons. There are now paradox dragons that are only het trans, but the vast majority of them are still visually trans. I am not aware of any paradox dragons that are not at least het trans.

DUNNER

I am a big fan of the dunner trait. I love working with it for the beautiful patterns it creates.

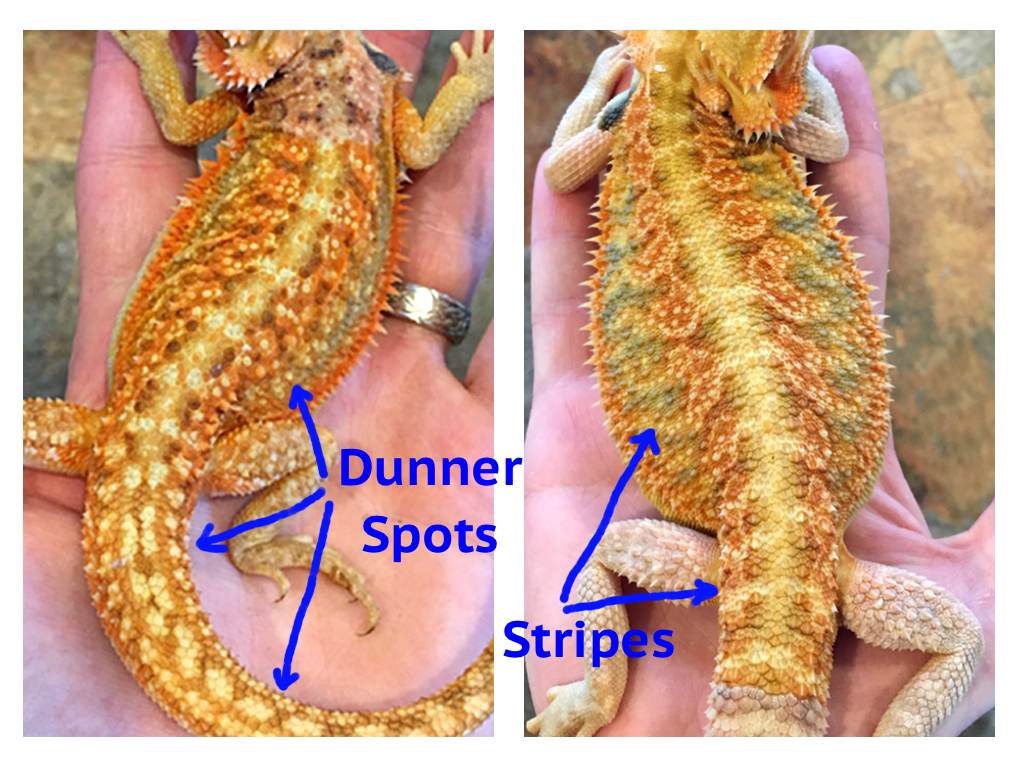

The ‘natural’ pattern for bearded dragons is to have stripes that start at the spine and run out to each side. Even if the pattern is subtle, it still has a side to side direction. The dunner mutation changes that.

By breaking up the pattern, the dunner mutation causes spots. Scales and spikes tend to be colored individually to form an intricate pattern of small spots. When dunners have a pattern with a clear direction, that direction tends to run from head to tail.

But what if a dunner is all one color? How do you identify them if there isn’t a pattern? Fortunately there are other characteristics that make identification easy.

The dunner mutation changes the direction of the scales. On the beard of a dunner the spikes point out to the sides. On normal dragons the beard spikes point down towards the belly.

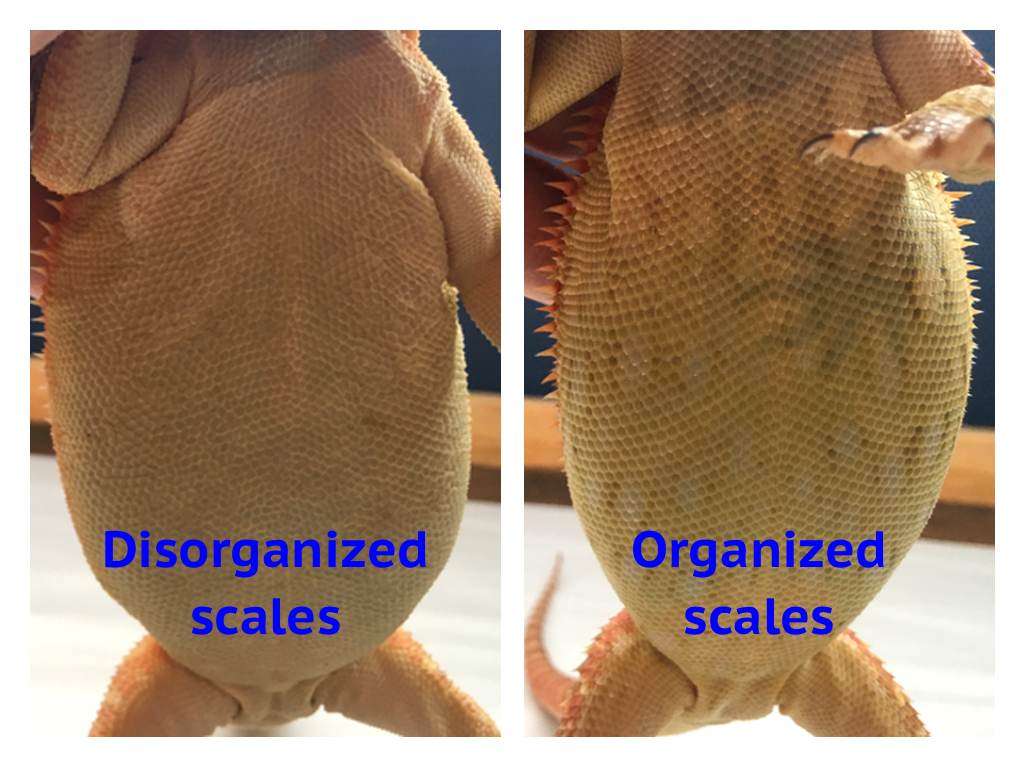

The scales on the belly of a dunner point in many different directions, causing them to look disorganized. On the rest of the body the scales and spikes are more raised and textured because of this misdirection.

A leatherback dunner won’t have spikes due to the leatherback trait, but she won’t feel smooth to the touch either. She will feel like gritty sandpaper because the dunner trait causes her spikes to grow in many different directions.

Dunners have a unique behavior that is not shown in other bearded dragons. After eating they tend to hold their food in the back of their throat for a long time, sometimes hours, before swallowing it. I have no idea why they do this.

Occasionally this behavior creates issues for hatchling dunners. They hold their food in the back of their throats and then regurgitate it later instead of swallowing it. Most dunners don’t have this issue and they grow just as fast and hardy as other dragons.

The ones that do regurgitate outgrow the habit by the time they are old enough to ship. They continue to hold food in the back of their throats throughout their life but are not negatively effected by the behavior.

GENETIC STRIPE

When it comes to stripes, there are a confusing number of different terms. Color stripe, genetic stripe, phantom stripe… Without good definitions for these terms, its enough to make your head spin.

The only stripe term that refers to a mutation is genetic stripe. Below you can see a group of genetic stripe hatchlings.

Genetic stripe is a dominant mutation that causes a clear racing stripe on each side of the spine. The stripes run all the way from neck to tail, and can often be seen extending into the tail. Depending on the dragon’s color the stripes may stand out boldly, or be less visible.

In all other cases where a dragon has stripes, that are not clear, straight racing stripes, you are NOT looking at a mutation.

Bearded dragons naturally have special coloring on each side of their spine in the form of large spots. In some dragons the spots are so large, that they are not separate from one another. Instead they blend into one another to form a continuous band of color.

These bands of color are caused by many genes working together, not any single mutation.

Dragons that have these bands of color, but do not have the genetic stripe trait, are sometimes labeled ‘color stripe’ or ‘phantom stripe’. Some breeders try to capitalize on names like these because they sound interesting. Labels are fine, but when you are picking out a dragon, put what you like above any label. Especially when that label does not refer to an identified mutation.

LEATHERBACK

There are two different mutations that cause leatherback. The first, and most common is a co-dominant mutation. Co-dominant means that its effect is more extreme in animals that receive the trait from both of their parents (homozygous), then animals that receive the trait from only one parent (heterozygous).

The second leatherback mutation is recessive. We will talk about that more when we discuss microscale dragons.

Leatherback dragons have one row of spikes running down each side of their body, as well as spikes on their beard and head, but they have little to no spikes anywhere else on their body. Their back and tail have smooth, uniform scales, and their legs also have little to no spikes.

As with any trait, there is variation from one animal to another. Some leatherbacks have small residual spikes on their backs that look more like enlarged scales then true spikes.

You may come across the phrases ‘Italian leatherback’ and ‘American leatherback’. These are outdated terms and don’t mean anything. Co-dominant leatherback was first discovered in Italy. Another co-dominant mutation which causes the exact same effect was later reported to be discovered in the United States.

Without genetic analysis there is no way of knowing if these really are two different mutations. There is no visual way to tell the difference between these two co-dominant mutations, if they even are two different mutations. One does not cause a dragon to be more smooth then the other.

SILKBACK

So far we have only talked about the leatherback mutation when a dragon inherits it from just one parent. A dragon that inherits co-dominant leatherback from both of its parents (homozygous), is called silkback.

Silkback bearded dragons not only do not have any spikes, but they also do not have any scales. They only have scale-less skin; Skin that is very thin and very sensitive to damage.

It is unfortunate that some breeders still produce silkback dragons. Silkbacks have a lot of skin issues and are more easily injured. That is why I believe it is unethical to produce silkback bearded dragons. You will never see silkbacks being produced at Bearded Dragon Home.

All reptiles have skin. A reptile’s scales grow out of the top layer of their skin, similar to how hair grows out from the skin of mammals, and feathers grow out from the skin of birds. Their scales are protective and the skin beneath is not meant to be exposed.

Silkback bearded dragons need regular baths as well as lotion to help loosen shedding skin. It is very common to see silkback dragons that are missing toes or the end of their tail. This is because without a protective layer of rigid scales their shed skin is prone to drying and tightening around small body parts and cutting off circulation. A juvenile silkback dragon that is not bathed regularly to help remove shed skin, is a risk of losing toes and other body parts to this loss of circulation.

Silkback dragons are also sensitive to skin damage. A silkback dragon can never be housed with another bearded dragon. Even if there is no aggression between them, the other dragon’s nails will cut a silkback any time they come in contact.

Any other semi-sharp objects in the habitat that would not effect a bearded dragon that has a protective layer of scales, may cut a silkback dragon.

The silkback condition should be considered a genetic defect because the condition hinders their ability to live a normal, healthy life. It is also not necessary to produce silkbacks in order to continue to enjoy the leatherback trait. So long as only one dragon in a breeding pair is leatherback, then the pair will produce leatherbacks and ‘normal’ scale dragons, but no silkbacks.

The recessive leatherback mutation cannot be used to produce silkbacks. Only the co-dominant leatherback mutation can produce silkbacks.

MICRO SCALE

A micro scale bearded dragon is what you get when you combine the co-dominant leatherback mutation (heterozygous) with the recessive leatherback mutation (homozygous).

Micro scale bearded dragons look similar to leatherbacks but have even fewer spikes. They do not have spikes on their beard or on the sides of their body that leatherbacks have. They may have a few small spikes on the sides of their body, but no more. The spikes crowning the back of their head are typically smaller then normal.

ZERO

Zero is one of three mutations that all result in patternless bearded dragons. All three of the patternless mutations are recessive.

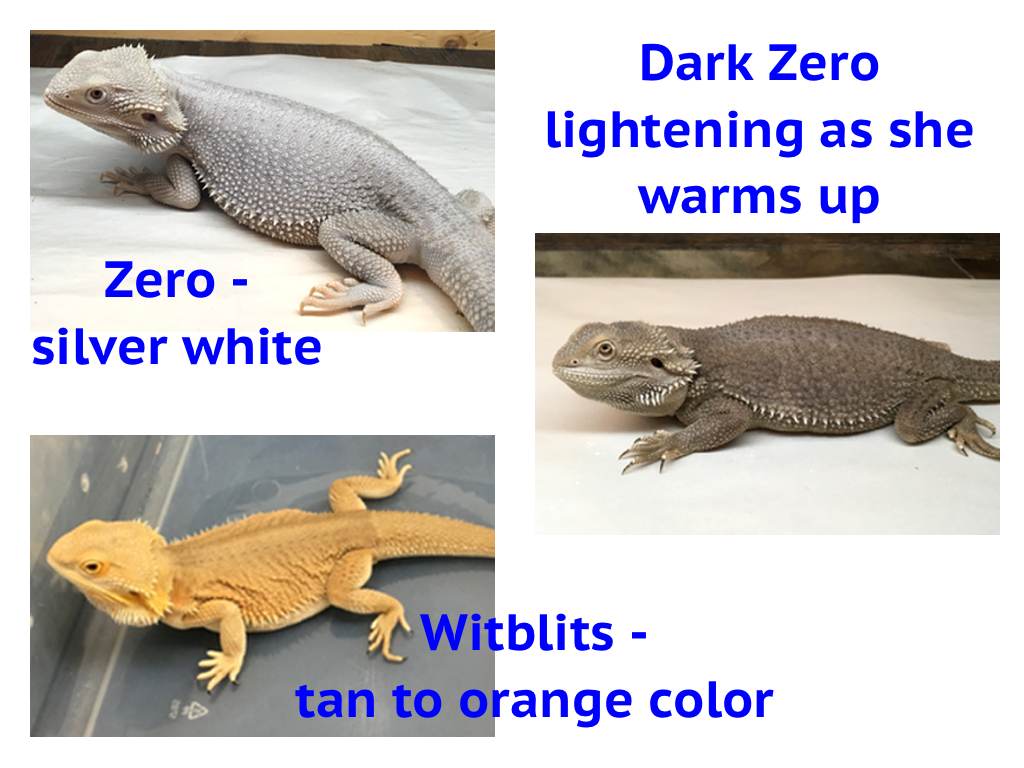

Zero is the most recent of the three patternless mutations to be discovered. In my opinion they are also by far the most beautiful of the three. Zeros are a silver off-white color, but they can also be darker shades of silver or gray.

Shown below are two zeros. On the left is the silver off-white of a high end zero. On the right is a darker zero that is just starting to warm up under her heat lamp. As she warms up lighter patches of color are developing, particularly on the top of her head and on her feet. As she continues to warm up she will become a lighter color, but she will not become quite as brilliant as the zero shown on the left.

Below we will discuss the witblits mutation and how to tell the difference between a witblits and a zero.

WITBLITS

Witblits is another of the three recessive mutations that cause a dragon to be completely patternless. Witblits was discovered shortly before the discovery of the zero mutation.

Witblits was discovered by a breeder in South Africa and means “white lighting”. There is some unfortunate irony in naming the trait ‘white lighting’. Not only are witblits dragons NOT white, but the name makes even less sense with the discovery of zeros, which are silver off-white. Oops!

Early witblits dragons were a relatively brown earth tone. While in a conversation with me, a fellow breeder once eloquently summarized why I had little interest in witblits saying:

“Zeros are silver and witblits are brown. Zeros look like money, and witblits look like mud.”

Fortunately the witblits trait has improved over time. Shown above is what the more high end witblits dragons currently look like. In higher end witblits, the more dull earth tone has been brightened to a sandy orange color.

SILVERBACK

Silverback is the last of the three recessive mutations that result in patternless dragons. They are the poor cousins of the patternless traits.

Having originated in Japan, the silverback mutation never gained much interest in the United States. Silverback was the first of the three patternless mutations to be discovered. However, witblits and zero, being far more popular patternless traits, have largely replaced any interest in the silverback mutation.

Despite its compelling name, silverback is a rather uncompelling mutation. Hatchlings are born with normal patterning, which fade to a patternless or near patternless appearance over several months.

Their final color tends to be a dull off white or earth tone. Their name evokes an image of a shiny silver white zero dragon, and unfortunately the silverback trait fails to deliver on that image.

Take caution when buying dragons that are advertised as possible het silverback. The silverback trait is extremely rare in the united states. These boasts are, at least in some cases, just fluff meant to capitalize on a name that sounds a lot more interesting than it really is.

Unless the breeder can produce photos of visual silverbacks in their breeding collection, which they probably can’t do, then it is very unlikely that the dragons they are selling actually carry the silverback mutation.

WERO

A wero is a combination of zero and witblits. Weros are homozygous for zero and also homozygous for witblits. They generally resemble zeros, but have splotches of darker color that usually appear on their back and tail.

ALBINISM

Currently there are no albino bearded dragons. The category is included here only to explain why white dragons are not albino. An albino is an animal that cannot produce any melanin, and because of that are completely white.

Albinos are all white, and have red eyes. The reason why their eyes are red is because there is no pigment to mask the blood vessels in their eyes.

All dragons that are white or nearly white produce melanin, and do not have red eyes. All reports of albino dragons that are rumored to have hatched, resulted in the dragon being weak or unhealthy and dying. There has not yet been a strain of albinism discovered that is viable for producing healthy, breedable bearded dragons.

LEUCISM

Leucism is related to albinism. Leucistic animals have a significantly reduced amount of melanin, but do not completely lack all melanin like albinos do.

Leucistic animals may be white, patchy, or just lighter then the normal color of the species. Leucistic animals do not have red eyes. Only albinos have red eyes.

Hypomelanism, zero, and whitblits are all different examples of leucism. They are all examples of a mutation that reduces the amount of melanin the dragon expresses.

White color morphs which may go by the names snow, ice, and blizzard are not leucistic. These color morphs are the result of many genes working together, and were developed through many generations of selective breeding. Their white coloration is not caused by a single genetic mutation.

Get in touch

Cute Bearded Dragons for Sale